Below, we look at warnings from the inverted yield curve, and it’s not as boring or as fun as you think.

Signs of Dismay

To say that debt is a problem ($90T in combined US consumer, federal and corporate) and that the bonds that represent them are an even bigger problem would be a comical understatement.

Given that natural supply and demand for Uncle Sam’s IOUs has been replaced by years and years of central-bank “accommodation” (i.e., printing money out of thin air at the Fed to buy otherwise un-loved US IOUs from the Treasury Dept), it’s more than fair to say that the “bond market” is effectively nothing more than a Fed-market.

Full stop. Period.

And given that our openly fraudulent Fed has spent years backstopping the greatest wealth transfer in history by replacing (killing) capitalism with feudalism and destroying what little remnants of natural price discovery that remained in the credit markets, it’s equally fair to say that our faith in that Fed is anything but robust.

In fact, to fully unpack the nearly endless stream of the Fed’s open mismanagement of the bloated bond market in particular, and the fatally inflated stock market in general, would require an entire book, which, thankfully, we’ve already written… (See Here)

Stated simply, the Fed has single-handedly and artificially managed (crammed, repressed, intervened, manipulated and distorted) bond yields and interest rates for so long via years of low-rate debt expansion that the US economy—and markets—are little more than a recession waiting to happen or a Titanic looking for an iceberg.

And as for that recession off our bow, the yield curve is screaming “iceberg ahead.”

Flashing Warnings from the Yield Curve

Ok. Ok…we know yield curve talk sounds kind of boring and/or complex.

But it’s actually fairly simple to grasp and, more importantly, it’s extremely important to watch given that every US recession since 1970 followed what the fancy lads call an “inverted yield curve.”

When a yield curve “inverts,” this means the yield investors receive for holding Uncle Sam’s IOUs for 10 years (i.e., a 10-Year Treasury) is actually less than what investors receive for holding a 2-Year Treasury.

If this seems crazy to you, you’re not alone.

After all, if you’re holding on to a 10-Year IOU, wouldn’t you expect to get more “yield” for the extra time (and risk) spent than you would otherwise receive for holding a 2-Year IOU?

But not surprisingly, years of un-natural Fed mechanizations have put us, once again, in this crazy scenario yet again, and based on both history and common sense, this means a recession in the next year or so is essentially inevitable.

Why?

Let’s dig in…

Yield Curves Matter

Last Tuesday, the spread between 2-Year and 10-Year Treasury Yields inverted. Most pundits called it a glitch and ignored it.

We were not ignoring it, and by Friday, it inverted again and has been distorted to levels not seen since 2007, which if memory serves correctly, came just before the markets fully puked in 2008.

Just saying…

In short, yield curves matter. They warn of “uh-oh” ahead.

As for prior (and similar) yield curve inversions in 1998 and 2006, they are worth a few paragraphs of compare and contrast (see below).

It’s All About “Liquidity”

As most professional traders know, everything about the markets is driven by “liquidity” (i.e., money flows), and when liquidity is running hot, bonds and stocks go up; yet when liquidity is running cold, bonds and stocks go down.

In fact, every market crisis is effectively just a liquidity crisis. As we see below, there’s going to be less liquidity as the tapering Fed has all but shouted this out.

Needless to say, when a central bank spends years and years as well as trillions and trillions of mouse-click-created money to buy bonds that no one else wants, that’s a helluva a liquidity hose, and it has been pushing up bond prices and hence sending yields lower (as yields move inversely to price).

But when that hose gets “tapered,” the fun starts to end.

Rising Rates Killing the “Fun”

Interest rates, which represent the cost of debt, rise and fall with bond yields, and given that DEBT is the sole wind beneath the US markets’ and economy’s tattered wings, interest rates really, really, really matter.

But here’s the rub. Banks make money by collecting interest. But when bond yields (and hence interest rates) are artificially repressed, banks make less.

And given that the Fed’s true and primary mandate and client (as well as creators) are banks not Main Street, this puts that oh-not-so-admirable Fed (and big bank brothers) in a pickle.

Banks lend less when the yield curve inverts, yet Wall Street takes greater risks with cheaper borrowing costs (i.e., lower interest rates) on short-term debt.

In essence, when yield curves invert, liquidity flows out of Main Street and directly into those noble and speculative canyons of Wall Street.

This creates temporary market “fun,” followed by great pain.

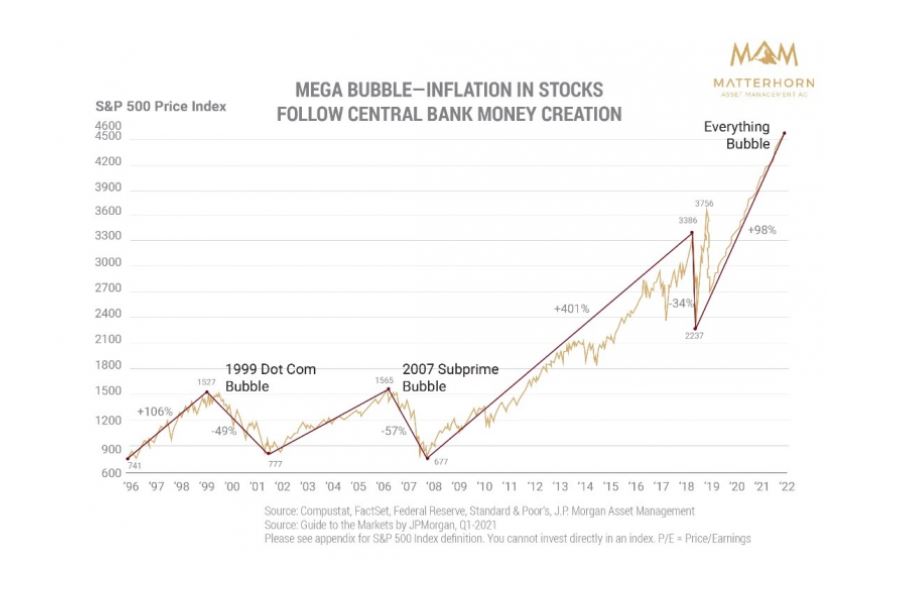

And given that Wall Street is already partner to the greatest and most over-valued stock bubble in recorded history, maybe more speculation is not such a safe bet at such times/highs, no?

After all, if inverted yield curves signal pending recessions, shouldn’t investors pause to think about that?

An Inevitable Recession

Furthermore, and notwithstanding the warnings from the yield curve, there are more than enough other issues happening here and abroad to make one worry about a pending recession, wouldn’t you think?

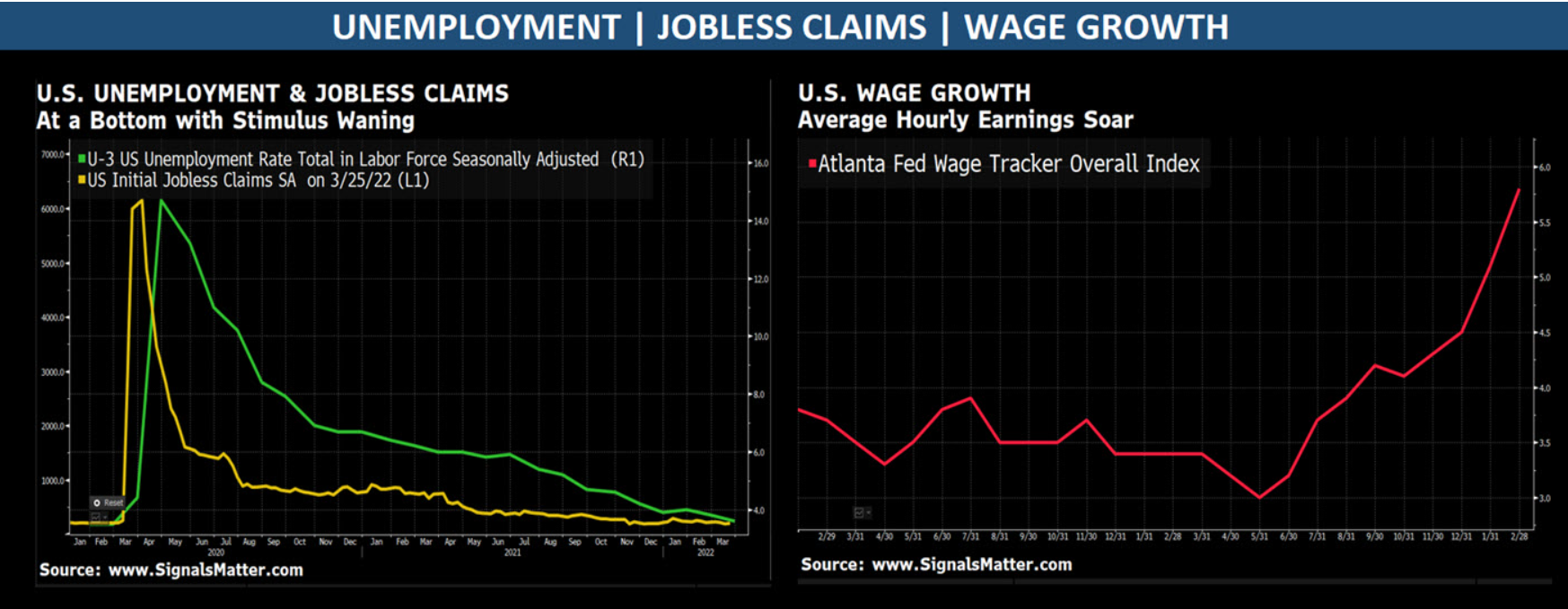

Even former NY Fed Chief, Bill Dudley, has openly confessed that “the Fed has made a US recession inevitable.”

But Dudley based this warning not on the yield curve, but on rising unemployment data and Fed tightening policies.

How Much Air in the Market Tires is Left?

Given that even Fed veterans and yield curve history are screaming “recession ahead!”–shouldn’t investors be worried?

After all, recessions can’t be good for a record-breaking and bloated stock market, even one now on a full-Fed respirator.

Ironically, and based on prior yield curve inversions in 1998 and 2006, markets actually went up rather than down immediately following a yield-curve inversion.

Part of this temporary euphoria stemmed from Wall Street binging/borrowing and speculating on lower rate debt, as described above.

That is, there was still a bit of air left in the tires of those 1998 and 2006 markets.

But then again, not long after that 2006 inversion, the tires went “pop” and then altogether flat by 2008, remember that epic implosion?

And in 1998, just after the yield curve inversion, the infamous Greenspan rate cuts sent dot.com markets to the moon just before they cratered to the ocean floor by April of 2000.

Remember that?

In short, the nice little “booms” (i.e., “fun”) that temporarily followed a yield-curve inversion were defined shortly thereafter by epic “busts.”

Will the current scenario be any less predictive—i.e., “no fun”?

Simple as A, B and C

Well, if you factor together three simple indicators, the future is not that hard to see.

By this, we are talking about the critical interplay of: A) 2-Year Treasury Yields, B) 10-Year Treasury Yields and C) the Fed Funds Rate.

Back in 1998, for example, when I was pocketing an un-deserved fortune in the NASDAQ bubble, we nevertheless remembered a few rumblings from Long Term Capital Management’s Asian exposure and a Russian default crisis, which prompted a 1998 yield inversion followed by the Greenspan Fed cutting rates and sending my fund’s NASDAQ holdings moon-bound.

That was fun.

Thereafter, the Fed attempted 6 gradual rate hikes in 1999 and 2000, which caused the yield curve to invert again in 2000. Thereafter the NASDAQ famously tanked.

That was not fun.

Needless to say, the Fed stopped hiking rates and eventually the yield inversion ended once again.

In both cases, 1998 and 2000, the inversions occurred when the Fed Funds Rate (C) was at the same levels as the 2-Year Yields (A).

Stated simply: The inversions ended because the Fed cut rates. But today, as we see a 2022 yield inversion, the Fed is promising to raise rates with very little room to do so.

Should We Be Worried?

Now let’s look at the 2006 inversion.

Once again, it took place when the Fed Funds Rate was at roughly the same levels as the 2-Year and 10-Year Yields (i.e., A, B &C were equal). The Fed had been raising rates every month to get there.

But not long after 2006, say around 2008…the markets suffered an epic implosion.

That was not fun either.

And, as expected, the Fed famously cut rates to stem the fire.

But the 2006 inversion was unique.

By the summer of 2007 (just a year prior to the 2008 implosion) the Fed Funds Rate was above 5%–far too high for those toxic sub-prime bonds floating around the markets like mini timebombs.

By 2008, again, everything tanked.

But looking more carefully at the yield inversions of say 2000 and 2006, we see in both cases that just after the yield curves inverted, something broke just months afterwards which forced the Fed to cut rates, at a time when bond yields and Fed Fund Rates were roughly the same and the economy seemingly “fine.”

The 2022 yield curve inversion, however, is critically different than these prior examples in that the yields on the 2-Year and 10-Year Treasuries (A and B) are far higher than the current and grotesquely repressed Fed Funds Rate (C).

In short, the Fed has very little rates to cut, as they’ve bene artificially repressed for so long at such lows.

Why is this important?

The market knows the Fed is going to raise rates so the C catches up with A and B.

In plain English, the market knows that these well telegraphed rate hikes are going, as described above, “to make a recession inevitable,” which will stifle growth as well as stock prices.

So yes, we should be worried.

Looking Ahead

Based on the foregoing patterns, we can expect the current yield inversion (i.e., warning) to correct and move outside of inversion as longer-term Treasuries (i.e., 10-Years) suffer in price declines (and hence rising yields) as the now fully-cornered Fed engages in its much forward-guided “taper.”

But as we’ve warned, saving the yield curve from inversion likely means yields and hence interest rates (A, B & C) will rise and trend up, which like rising shark fins, will be a familiar death knell to the current everything-bubble as early as 2023.

Folks, when everything “fun” about our economy and market bubble is driven by debt, that fun ends the moment the cost of that debt (i.e., yields and rates) rise.

Fairly simple, no?

Needless to say, the Fed’s openly shameless experiment of constant liquidity (i.e., money printing) is clearly insane, but insane doesn’t mean the Fed is stupid.

They see the recession ahead as well—after all, they created it.

And knowing that the current everything bubble is poised to burst in the coming years, that is precisely why they are scurrying to raise rates now.

Why?

Because they’ll need those Fed Fund Rates (C above) to rise high enough so that they will have something to “cut” when the next market implosion hits us all.

This, of course, is highly reminiscent of 2018, when Powel desperately sought to raise the Fed Funds Rate throughout the year so that he’d have something, anything, to cut when markets puked.

But as December of that same year reminds us all too well, the market simply can’t take those rate hikes, however “gradual” or “forward-guided” they may be.

Stated simply: Our debt-soaked system is just too broke to stomach the rising cost of debt or a rising Fed Funds Rate.

When the current “fun” ends, is your portfolio prepared? If not, join us here.